Brielle is the Fall 2022 Dream & Scheme Horse Show Award recipient, sponsored by Dreamers & Schemers.

I was an equestrian before I was anything else. I have always had an innate fascination with horses. Before I could walk, I was eagerly crawling toward horse toys. As I grew older, my love for horses grew even stronger. My mother assumed every little girl’s dream room was an embellished pink room adorned with Disney princesses. She soon learned it was the opposite for me after I begged her to switch my princess-themed room to a horse-themed one. My mother knew she had to satisfy my adoration for horses and took it upon herself to find me a place to ride. Unbeknownst to me, this would be the most meaningful experience of my life as I met an equestrian whom I would never forget.

Malcolm Dickinson was the name of the cowboy who changed my life. Malcolm was an older man who kept no value in his appearance and wore tattered brown boots and dirt-stained jeans every day. He drove around with goats in the passenger seat of his ramshackle truck and bathed in the water troughs of the horse pasture. Nevertheless, Malcolm was a knowledgeable equestrian who thoroughly understood the nature of horses. He was eager to fill my youthful brain with the information he had obtained throughout his long life, and I was equally eager and intrigued to learn. Although these untamed qualities of Malcolm were engrossing, it was not what initially caught my attention; instead, the first thing that sparked my interest in Malcolm was that he was an African American equestrian.

My passion for horses only furthered with Malcolm. He taught me the ins and outs of navigating a less-than-ideal world of equestrianism as an African American. I spent every evening at Malcolm’s ranch learning and loving the world of horses. Malcolm was so impressed by my interest and hunger for knowledge that he and I eventually convinced my mother to buy me my first horse by the age of nine. Malcolm made this possible by allowing us to purchase a horse from him at a much-reduced price and much hard work on my part, mucking stalls, feeding, and exercising his herd. The more I became involved, the more horses I wanted for my own. Eventually, my mom and I became the proud owners of 5 horses. By age 13, I was teaching local youths what Malcolm had once taught me through lessons at a leased barn and volunteering our horses at local festivals providing horse rides and petting experiences.

I am sure everyone knows the saying, “life gets in the way,” I would use this to describe precisely what happened to me. Standing 6 feet tall at age 14, I was lured away from my horses and into the world of basketball, a sport that was not my passion but a way to pay for college. I was often reminded that being an African American equestrian would not afford any opportunities to pay for my education. As a result, basketball consumed me, causing me to spend long summers with my travel team far away from the barn. By my senior year, I received several scholarship offers for basketball and decided to attend a two-year college for financial benefit, leaving my true passion behind. While in school, I struggled to acclimate to my new environment in a primarily restricted COVID world. I found myself self-isolating from others, questioning my identity and, more significantly, my purpose. I ultimately decided it was not beneficial to continue beyond the second year playing basketball because my heart was not in it but rather with my horses. With my time no longer consumed by basketball, I realized that the young girl who was once a passionate rider and who loved sharing that passion and knowledge with others still lived inside me. I yearn to get back to my true passion.

I am currently a part-time student pursuing a biology major, with the ultimate goal of attending veterinary school and becoming a Doctor of Veterinary medicine specializing in equids. Through my degree, I would like to continue my education in the equine industry to better assist other underrepresented youth in pursuing their passion for horses and advancing the veterinary field in terms of equity. My recent anxiety diagnosis, coupled with my father being 100% disabled after serving in the military for 23 years, has unfortunately resulted in financial obligations that caused me to take the current semester off from school full-time. I will resume my education endeavor as a full-time student in the spring semester of 2023 at either The University of Texas or Baylor University.

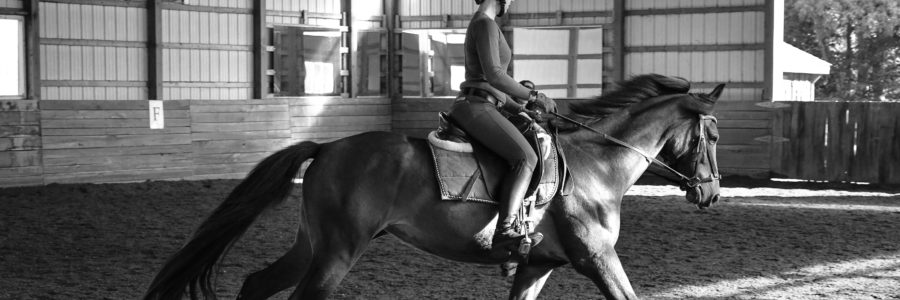

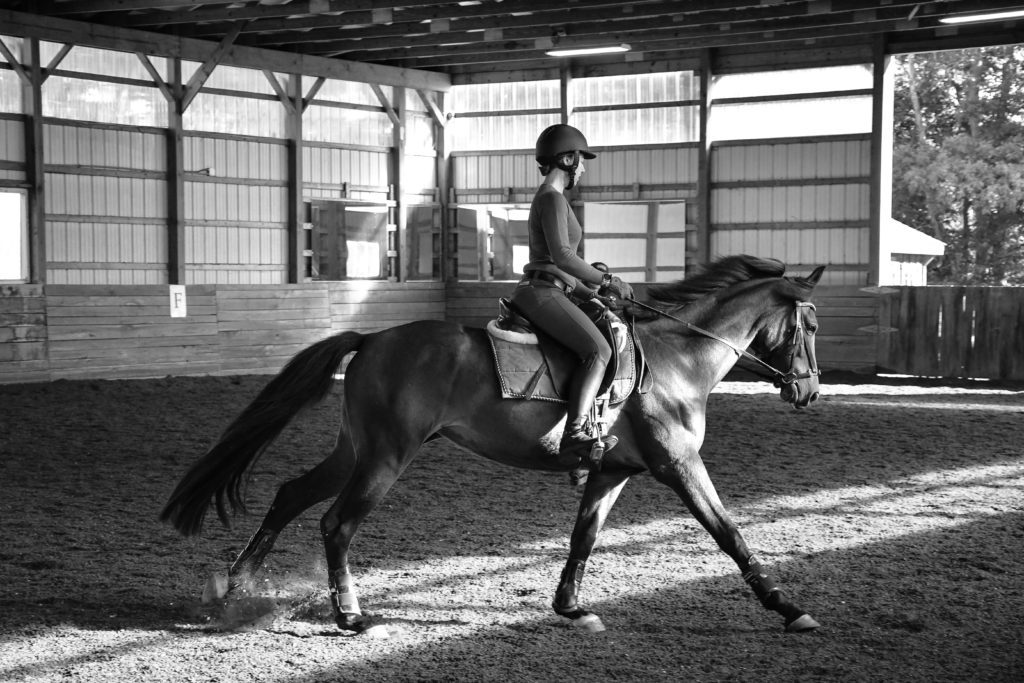

My current riding goals include joining a riding club, improving my riding skills, and furthering my horses’ training. Both of my prospective Universities offer riding clubs, which I wish to join. Jointly, I want to begin formal training for my horses, who have unfortunately suffered the seemingly untameable “barn sour” fate due to our inability to afford quality training. Training for my youngest horse, Diamond, would be geared toward barrel racing with the hopes of eventually competing at the AQHA Barrel Racing World Championship. Additionally, having limited interactions with my horses over the past two years, it would be best if I began training to tune up my riding skills at Peaceful Acres, a local ranch where I have had the opportunity to volunteer. The Optimum Youth Equestrian Scholarship would be a stepping stone in that direction.

Receiving the Optimum Youth Scholarship would help to relieve financial strain and allow me training opportunities that I could not afford due to the cost of college tuition and at-home obligations. Moreover, a mentorship would serve as an opportunity for growth in both my equestrian and professional goals. Most importantly, this scholarship would serve as a vessel to help launch me toward achieving my lifelong dream of being a successful equestrian.